The previous post discussed the calming cycle theory by Welch and Ludwig. Welch’s study demonstrated that an adaptive emotional connection could be regained in premature infants and mothers. They could measure this based on an automatic calming effect on both. But how does this happen naturally?

Effect of person: emotional programming?

An insight into how individuals learn came from prior research on dog behaviour. Pavlov and Gantt studied animal behaviour using dogs, and part of this work involved making dogs anxious. However, they noticed that if the dog’s handler petted it, its heart rate would slow. After repeated petting sessions, a dog would become conditioned to have a lower heart rate in the handler’s presence. This calming effect was so distinct that they called it the “effect of person.” This was not a top-down cognitive process, so what was going on? Is this a type of emotional programming?

Autonomic nervous system – the non-conscious self.

We have two major parts of our nervous system – the “central” and “autonomic” nervous systems. The central includes our brain and spinal cord, which includes our “thinking” cognitive parts. The autonomic is more “autonomous”; it includes the sympathetic, fight-or-flight system and the parasympathetic, rest-and-repair nervous systems. The effect-of-person behaviour is an example of autonomic nervous system learning based on conditioning. It’s a “when that happens, automatically do this” non-conscious kind of learning.

Dual track perception

We operate with a two-track stimulus-response system. One track is at the autonomic level. It’s the fast track, allowing us to react quickly without conscious or thinking. A good example of this is our orienting response. You automatically turn your head toward a noise you weren’t expecting. THEN, you will think about it. This thinking part is the second, slower track. This is where you would recognize the noise or not and decide whether to ignore it. But even this orienting response can be “conditioned.” Once you learn that a noise is safe to ignore, you will not orient to it; you won’t even register it. It will be a stimulus, but you have learned to ignore it and have a different orienting response. Researchers understood the importance of this. Humans could “learn” behaviours at this level. Is this part of our emotional programming?

Pregnancy: the start of emotional programming?

Infant development is a highly interactive process. The fetus is in a reciprocal process with the mother, not just passively growing. The researchers believe that mothers and infants condition each other during pregnancy to co-regulate and co-calm. The infant becomes conditioned to the sound and smell of the mother. Importantly, it sets up an automatic “approach” orienting response to the smell, sound, and touch (warmth) of the mother. The mother and infant have both learned to approach each other automatically, which is the best way to ensure the survival of the newborn.

The premature experiment

With all the advances in medicine, we have been in a period where premature babies survive. What Dr. Welch noticed, however, is that some premies and moms do well, and others don’t. She wanted to understand what was happening, as not doing well had negative consequences for both mother and child. What could explain this difference in neonatal intensive care units where all infants and moms had access to tremendous care? As it turns out, it was the quality of the mother-infant emotional connection.

Disrupting the normal attachment process

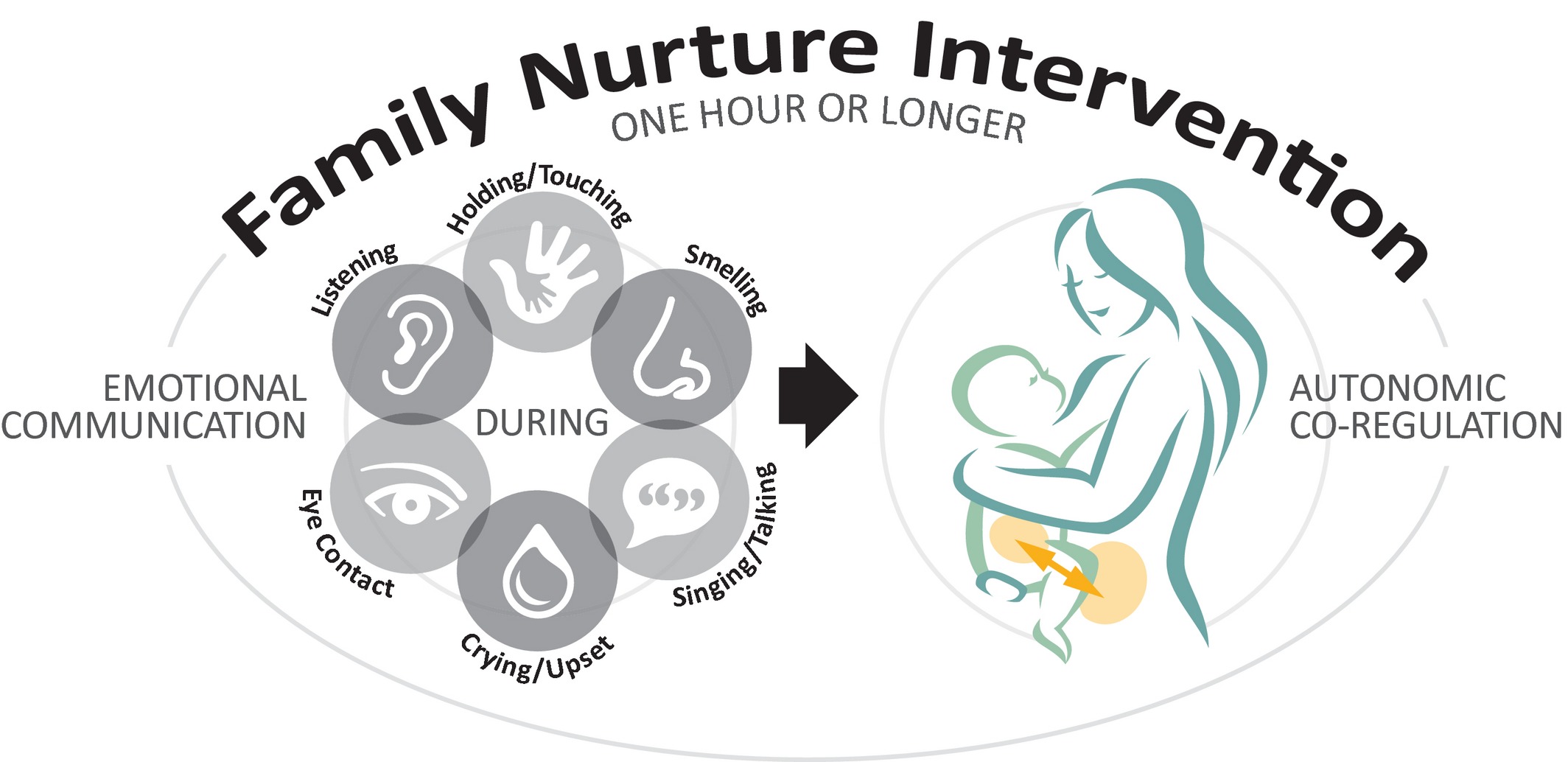

Mothers and infants naturally “attach” to each other during a normal healthy, full-term pregnancy and post-natal mothering period. This is a natural process seen in other animals. This comes from the mother and infant’s adaptive “approach-orienting” behaviour. Disrupting this process can cause an “avoidance” maladaptive pattern. This can cause a “difficult” infant and a stressed, upset mother. The “attachment” becomes “non-attachment.” Welch developed the Family Nurture Intervention program to re-condition the mother’s and infant’s autonomic nervous systems. (It works – see the previous post.) This intervention conditions an approach-type attachment, restoring the adaptive approach-orienting learning. This is what the Calming Cycle Theory is about.

Autonomic socioemotional reflex ASR – emotional programming?

The researchers propose that a specific type of conditioning occurs in this situation. They have named this the Autonomic Socioemotional Reflex (ASR). It is conditional co-learning and co-regulation that take place at the level of the autonomic nervous system. It’s “socio” because it’s social; it involves relationships, starting with the mother and infant. It is emotional because it involves behavioural responses. (Emotion in nature is about behaviours, not feelings.) It’s a reflex as the response happens automatically, without conscious intervention.

The developmental process leads to greater autonomy.

The ASR leaves little room for autonomous behaviour. It starts in the womb and continues after birth. I believe it is an aspect of our emotional programming: the programming that influences how we behave in relationships. Over time, it supports the infant to be more self-regulating and more autonomous at a physiological level. As the child grows up, this foundation helps them control their emotions and behaviour more. The calming “effect of person” is one of the first things we learn; it is always with us. The challenge is learning not to be dependent on others but to be able to calm ourselves. Enjoying the calming “effect of person” is a good thing. Being governed by it is not.

The development path of humans goes from fused and dependent to autonomous and interdependent. We see this on the physical level first. Our emotional and psychological levels follow. We become more separate but, ideally, connected. It’s good that we can calm each other. But we need to also be able to calm ourselves. We can enjoy our contact with others, but without being governed by it. This is the process of becoming more differentiated.

Thank you for your interest in family systems.

Dave Galloway

dave.galloway@livingsytems.ca

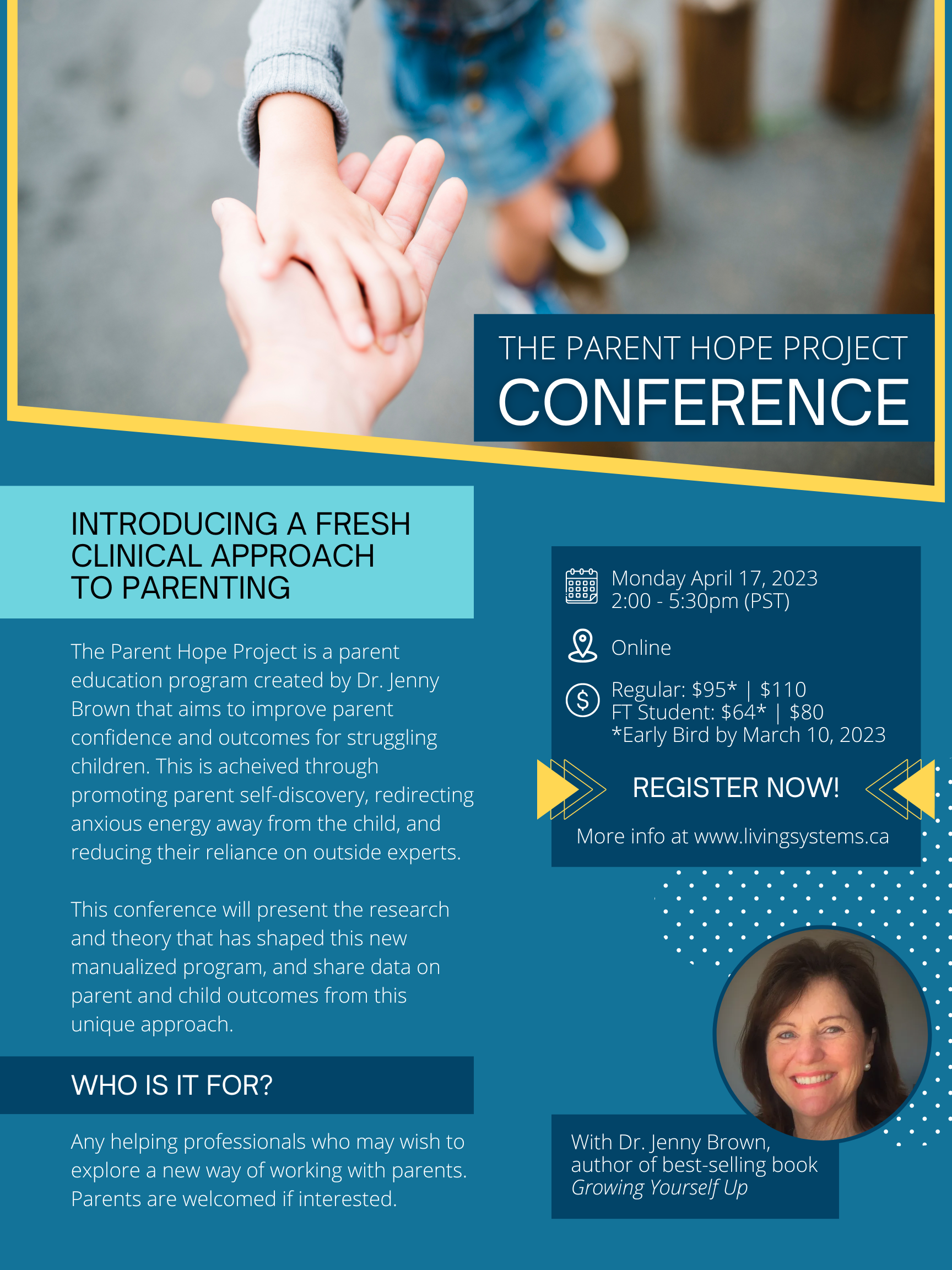

You can find out more about the Family Nurture Intervention here.

You can learn more about the autonomic socioemotional reflex here

Learn more about Bowen family systems theory here.