Bowen theory is grounded in the observation that the human family, like all of nature, is a living system. This means that individual members and the group as a whole influence one another’s functioning in many complex ways. The development of each member as a person, their resulting health and happiness, and the quality of connection with one another in the family unit are impacted by this interdependence, for better and for worse.

A second core observation is that individuals and families as a whole vary greatly in their ability to develop in ways that contribute to both the betterment of themselves, their families, and their society. There are many factors that impact an individual’s and a family’s ability to act in the best interest of oneself, one’s family, and one’s society, all at the same time. The level of emotional/cognitive integration in our brain, the level of chronic anxiety we carry and sustain, the degree of cut-off we have from important others are all factors that influence our ability to think, feel and act in ways conducive to an optimal outcome for ourselves and to our families and communities.

The Bowen Center

The Bowen Center for the Study of the Family is the organization that Dr. Bowen founded and directed. It is a valuable source of material related to Bowen Theory.

Bowen Theory: Dr. Bowen and the theory

Murray Bowen Archives Project

The archive is a valuable collection of resources for anyone interested in Bowen family systems theory. Here are some useful links:

An introduction to Bowen Theory: Bowen Theory Introduction

The key concepts

of Bowen theory

@2006 by Molly Jonsson

01. Differentiation

The term differentiation comes from biology. It is the scientific concept that most closely matches the processes Dr. Bowen observed within and between families. People vary across a broad continuum in their ability to function as emotionally separate individuals while in good emotional contact with important others in their families and workplaces. This is a naturally existing continuum that develops over several generations. It is neither bad nor good; it just is.

At one end of the continuum are individuals who are the most underdeveloped as persons, the most relationship-focused. Having the least self, they tend to live life reacting to others rather than out of their own well-defined beliefs and principles. They have little tolerance for short-term discomfort and delayed gratification. Short-term urges tend to dictate their lives at the expense of longer-term goals and gains. They are very sensitive to what others think about them. Feeling and anxiety states tend to dominate their behaviour and decision-making. This leads to swings between being overclose/positive and overdistant/ negative. Their behaviour is often at the expense of someone: themselves, their loved ones, employers, and friends. These individuals tend to have the most life problems.

At the other end of the continuum are those most fully developed as persons with the most self. They have well-thought-out beliefs and principles. Their behaviour matches these beliefs and principles most of the time. Functioning consistently in all their life roles and responsibilities unless their stress level is high comes naturally. They can experience strong feelings and anxiety states without losing their capacity to think and act more objectively and in the long-term best interest of themselves and others. Assuming high levels of self-responsibility they take on leadership roles in family, workplace and society.

02. Chronic Anxiety

Chronic anxiety refers to the habitual, automatic ways humans react when perceiving a life situation, most often a relationship interaction, as threatening. One may not be aware of feeling threatened. For many, this perception of threat happens below the awareness level. The individual starts eating, drinking, smoking, feeling bored, seeking a rush, needing action – to move, change, run, argue, fight back, or the opposite – avoiding, going passive and helpless, etc. These responses are both instinctual and learned coping strategies. Unfortunately, they usually reinforce greater levels of chronic anxiety and stress.

The formation of these automatic, chronic reactions can begin, possibly in utero, but certainly at birth. The child is equipped at birth to respond to internal and external cues for surviving and thriving. When the child’s needs are met in a manner that is realistic to the facts of those needs, the child’s focus will remain primarily cued to him or herself. When the child’s needs are defined and met more out of feeling states in the caregiver, a mismatch will develop between the child’s true needs and the caretaker’s efforts to meet those needs. Parent and child behaviour quickly becomes reciprocal. The child learns to focus more on the relationship process than on himself or herself.

Role of Perception

The parents’ and child’s perceptions of need come more from internal feeling states than the child’s (or later, the parent’s) factual needs. The child’s self-knowledge and self-development become compromised, more or less, over time. The patterns of responding to and out of relationship anxiety become automatic and chronically stressful. It affects all levels of the person’s functioning – from cellular responses in the gut, heart, skin, etc., to the psychological and social mechanisms for survival. These learned responses contribute to the development of the short-term coping responses listed in paragraph one.

03. Emotional System

The concept of an emotional system is core to understanding Bowen theory. The term “emotional” is familiar to most people. However, its meaning is different in Bowen theory than in its usage in society. In society, this term is commonly used as an equivalent or substitute for “feelings.” In Bowen theory, feelings are just the conscious tip of the iceberg that is the emotional system.

Dr. Bowen used this term to refer to all of the hard-wired physiological, psychological, and social mechanisms that have evolved in individuals and families to maximize their own and their loved ones’ chances for survival. It includes all of the internal and external interactions and reactions associated with our need for food, water, sleep, shelter, territory, protection from harm, mating, reproduction, and nurturing of young.

The term “system” refers to the complex interdependence and impact members of a family and larger social groupings have on one another and on the group as a whole. The needs of and for others, combined with individual needs and differences, are an automatic and ever-present source of tension. This tension and the instinctual and learned ways individuals and families deal with it lie at the heart of the concept of chronic anxiety.

04. Triangles

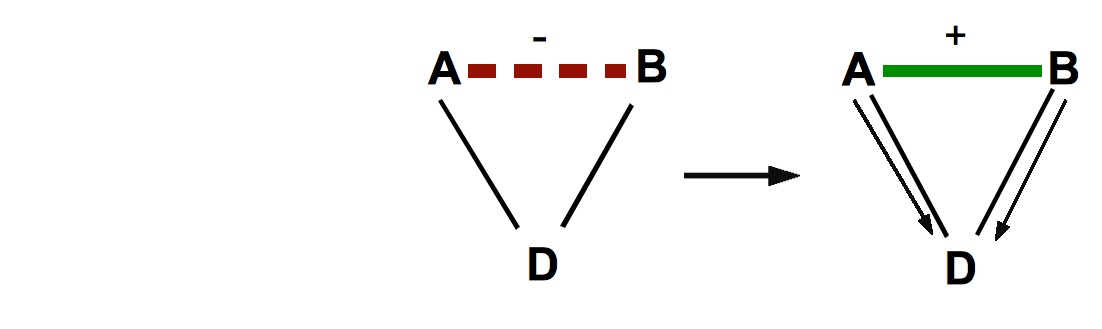

One of Bowen’s observations took centre stage in his understanding of humans as fundamentally systemic in nature. He watched the ever-present shifting of anxiety and roles within the basic unit of parents and children (and other social groupings). A major mechanism for shifting, fueling or calming that anxiety he called “triangles”.

Dr. Bowen described a two-person unit (A/B) as unstable. Two individuals have more or less difficulty being with one another and each keeping their focus on their own thoughts, feelings, behavioural choices. The first one to become anxious in this togetherness (A) will shift the focus onto someone else (D). The third person is drawn in (literally or figuratively) serves to ease tension between A + B. One triangling pattern is for A to relieve the tension with B by seeking a new and more secure, inside position with D. If D responds to this overture, then A and D form the new inside and the tension shifts from A/B to B/D.

Another pattern is that A+B can deny the unresolved tension in their relationship and begin to focus on D as the ‘problem’ or the ‘enemy’. They then form a more secure inside position with one another by having a common issue with D. Thus the tension between A+B lowers and the tension/stress builds in D as she/he is focused on as the problem.

05. Nuclear Family Emotional Process

This concept has two important dimensions to it: 1) the nuclear family and 2) the emotional process.

Emotional Process

This refers to the automatic, hard-wired sensitivity and accompanying anxiety reactions humans have to one another – from the level of our cells to our psychological and social reactions and interactions. In a family, these sensitivities can be heightened such that a particular response in a loved one can be seen as a major problem and the same response in a stranger is not noticed or reacted to as a problem.

Nuclear Family

The nuclear family is the basic emotional unit of a family system. The traditional form of this unit is comprised of husband, wife and one or more children. When the differentiation level of the couple is higher they will have more automatic capacity to manage the anxiety of their sensitivities – fears, disappointments, unrealistic expectations, etc.- with one another. They will have more capacity to resolve these tensions and differences. A less well differentiated couple will chronically generate more anxiety/stress around these same issues and have less effective means for resolving them.

When the level of chronic anxiety exceeds the coping capacity of the unit, the result is symptoms in the most vulnerable area of the family unit. This could mean symptoms in a spouse, in the couple relationship or symptoms in one or more children (see Nuclear Family Projection Process). There are three broad categories of individual symptoms: a) physical; b) psychological/psychiatric; and c) social. Symptoms in the relationships include conflict, distancing toward or including cutoff, and triangling. Triangling can move up into the extended family, out into the workplace or an affair or through projection down toward the children.

06. Nuclear Family Projection Process

When parents cannot deal with their undifferentiation and its accompanying anxiety between themselves, one (or more) of the children can be pulled into the tension in a way that, over time, compromises the normal development of a self in that child. Children can be triangled into the tension by one parent taking the child’s side over against the other. Children quickly begin to play their part in this process. Over time, this can result in the child viewing one parent in an overly positive light and the other in an unduly negative light. The difficulty for the child is that their energy for the development of self, to some extent, gets directed more to maintaining one’s position in the triangles than to their natural life course.

Triangle Patterns

The triangling pattern that most compromises the child’s development of self is one in which the parents ease the anxiety in themselves by denying their underlying weakness and colluding in seeing the problem as in the child. This automatic projection process includes the hard-wired survival response mechanisms for solving a perceived problem: assess, diagnose, and treat (fix or solve).

For example, a parent with unresolved anxiety around social situations and fear of rejection can deny this problem in self and focus anxiously on this as a problem in one’s child. The normal rejections and struggles of a young child’s social interactions are then perceived as abnormal and needing solving by the parent. The child picks up on the anxiety in the parent and begins to respond more to the parent’s anxious focus than on their natural strengths and abilities. Over time, the perceived problem in the head and feelings of the parent become a real problem in the development of a self in the child. The second parent intensifies the process by actively or passively following this view.

07. Sibling Position

One significant factor shaping individual family members’ functioning is their sibling position. Dr. Bowen incorporated the research on sibling position done by the late Dr. Walter Toman, an Austrian psychologist. In Bowen theory, sibling position represents both the work of Dr. Toman and Dr. Bowen’s understanding of the impact of the family projection process on the developmental course followed by a child.

Sibling position appears to be one of nature’s ways of enhancing survival by evolving different roles and positions. This results in forming family leaders and followers and all combinations in between. Each position naturally develops certain predictable strengths and weaknesses. The emotional process in the nuclear family unit can result in the individual in one sibling position being more vulnerable to the family projection process. The result is the impingement of the natural development-of-a-self process for the individual in that sibling position.

The following exemplifies an emotional process acting on a particular sibling position. Eldest children are naturally trained to take on greater leadership and responsibility. This is both in and for the family in the next generation. If the family projection process is on the eldest, the natural eldest abilities can be exaggerated or weakened. However, if weakening is the result, the usually capable and accomplished eldest functions more toward the helpless youngest. When exaggeration is the pattern, the eldest’s behaviour takes on the harsher side of leadership. For example, dominating, domineering, bossy, authoritarian behaviours.

08. Emotional Cut-off

Distancing is one of the hard-wired coping mechanisms for dealing with real or imagined threats to one’s well-being. We know it most stereotypically as the flight component of the stress response. The Nuclear Family Emotional Process includes the mechanism of emotional cut-off.

Individuals within families vary in how they use distance as a major coping mechanism. Distance becomes entrenched as a way of life in a multigenerational family system. With this, the older and younger generations end up emotionally cut off from one another. This often includes geographic distancing. However, living far apart doesn’t necessarily mean being cut off. The important criterion is that important aspects of one another’s lives are openly discussed and responsibly acted upon.

Humans need a certain quantity and quality of emotional contact with important others to function responsibly. Individuals who are emotionally cut off from their families tend to use their workplace and friendships as a substitute family. Research on emotional cut-off seems to corroborate one Dr. Bowen’s observations. He found that the family’s emotional system is a more effective emotional field with which to be in active contact. In these studies, grandchildren and great-grandchildren were shown to be the freest in pursuing a responsible life course when they had active emotional contact with the previous generations.

Defining a Self

This concept represents the application of Bowen theory in all areas of life. It requires a long-term effort to live the principles of differentiation. Differentiation as a process involves developing the strength to define oneself in one’s important relationships. It also involves gaining a greater ability to manage one’s anxiety-driven reactions. Relationships with one’s family, co-workers, and friends are all important in defining oneself. This, in turn, contributes to the best outcome for everyone. However, the emotional field of the family is the most effective for the long-term development of oneself as a person.

Take Responsibility for Self

Chronic patterns of reactivity in thinking, feeling and behaviour develop in the emotional field of one’s family while growing up. Adults can recognize the emotional shift in themselves when planning to visit their parents. Or in oneself as a parent when one’s child plans a visit home. The challenge of differentiation of self is to see and take responsibility for one’s part chronic patterns of reactivity. The integration of self at ever more subtle levels requires behavioural change. Shifts in the basic level of differentiation include shifts in our impulse control. This is from the cellular level to the psychological/social level of thinking, feeling and interacting. It has much to do with using our observational and self-reflective abilities to gain conscious control over our stress response. The psychological level involves our ability to think, perceive, speak and act based on facts versus feelings. Feelings can be helpful information when deciding what to do in a given situation. Rather than having feelings colour and distort perceptions and decision-making.