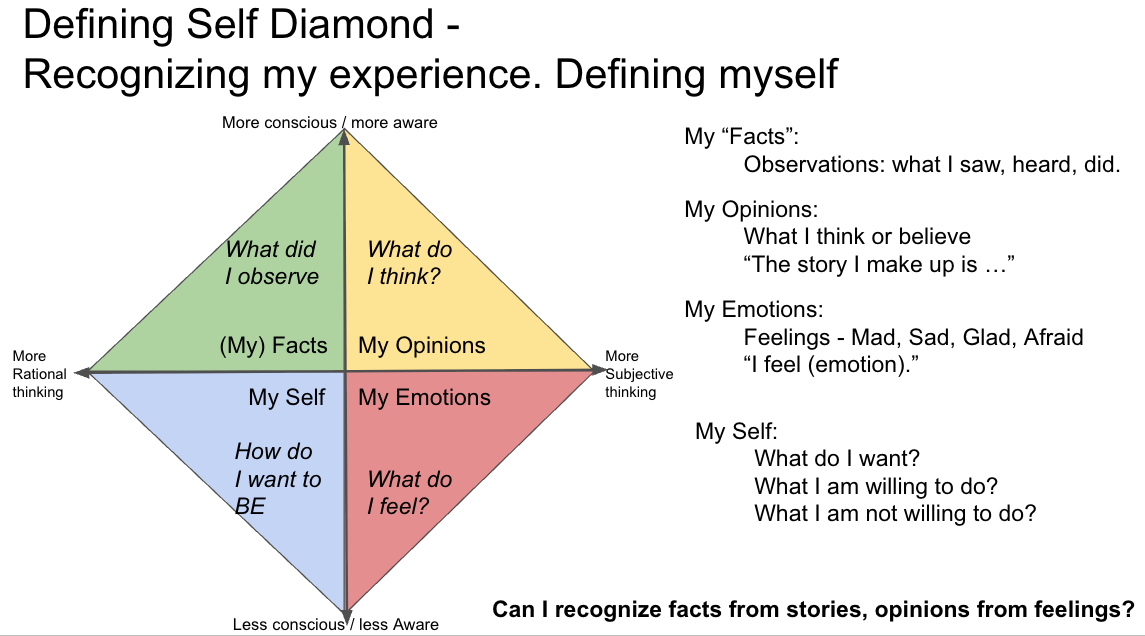

New research shows how our thinking can impact our gut health and trigger an immune system reaction. Chronic anxiety in relationships can activate this pathway. Define self could be more important to overall health that most people realize.

New research shows how our thinking can impact our gut health and trigger an immune system reaction. Chronic anxiety in relationships can activate this pathway. Define self could be more important to overall health that most people realize.

New research shows how our thinking can impact our gut health and trigger an immune system reaction. Chronic anxiety in relationships can activate this pathway. Define self could be more important to overall health that most people realize.