Why does it take time to change relationship patterns? What research says.

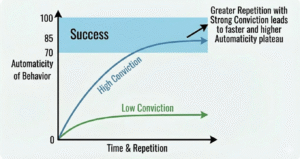

Changing automatic relationship patterns typically requires months of regular practice. Individual timelines will vary depending on the level of conviction to change, pattern intensity and frequency. This evidence comes from a 2024 meta-analysis of habit formation research. It supports what Bowen Family Systems Theory has observed clinically for decades: defining self, the ability to maintain a clear sense of self while staying emotionally connected, progresses slowly. More than intellectual understanding alone, it needs repeated practice in relationship interactions.

Research on health habits at a glance:

- Average time to automaticity: 106-154 days depending on behavior complexity

- Individual variation: 4 days to 11 months

- Success factors: consistency in stable situations, self-selected goals, and preparatory habits

When people work on how they function in their relationship systems, they often discover that progress is uneven and slow. From a Bowen family systems theory perspective, this experience makes sense. People are trying to change significant patterns like reacting less to a parent’s criticism or taking clearer positions with a partner. Even simple tasks like taking medications, take time to become a habit. Why shouldn’t complex relationship behaviours take more time. How can research on habits help us understand this?

Understanding differentiation in relationship systems

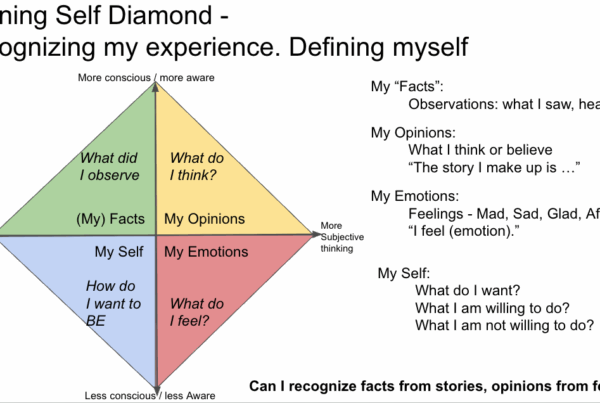

Differentiation of self means maintaining objective thinking and a sense of self while remaining emotionally connected to important others. It involves shifting from automatic emotional reactivity (like distancing or conflict) to more thoughtful responses based on one’s principles. These reactions aren’t simply psychological choices we make in the moment. They’re deeply ingrained patterns of emotional functioning. They developed and were reinforced over years of interaction in all our important relationships.

What habit formation research reveals about change timelines

A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis by Singh and colleagues, published in the journal Healthcare, examined 20 experimental studies involving 2,601 participants forming new health-related habits. The research team looked at how long it took for behaviours to become automatic. How long did it take to shift from requiring conscious effort and intention to become spontaneous and effortless?

According to Singh et al.’s analysis, the four studies that directly measured time to automaticity found habits require two to five months of continued practice. The average times ranged from 106 to 154 days depending on behaviour complexity. Most striking was the substantial individual variation: some participants formed habits in as few as four days, while others required nearly a year.

Success factors in habit formation

The research identified several factors that predicted success. Regular practice with similar situations mattered more than intensity of effort. Self-chosen goals strengthened more readily than assigned ones. Habits practiced in the morning proved more durable than evening habits. Positive emotion about the behavior, specific planning about when and where to practice, and small preparatory routines (like laying out exercise clothes the night before) all supported habit formation.

These findings challenge the popular 21-day rule for habit formation. Developing new automatic behaviours is a gradual process of neural rewiring that develops through repeated attempts in a stable context.

| Habit Formation Factors | Relationship Pattern Factors |

|---|---|

| Self chosen goal | Defining self on meaningful issue |

| Consistency in a stable situation | Find an identifiable situation and pattern |

| Morning versus evening | Observe the level of other stressors |

| Preparing | Determine an alternative response |

Source: Singh et al. (2024), meta-analysis of 20 studies

Why relationship patterns are harder to change than other habits

Defining self and habit formation involve different systems. Defining self is more about emotional processes than behavioural habits. The research on automaticity offers insights into why relationship patterns prove difficult to change.

Three key differences make relationship patterns harder:

1. The system responds to your change. Emotional reactions develop through repetition in predictable relationship exchanges and serve adaptive purposes. They maintain equilibrium and reduce tension short-term. When someone alters their part, the system resists because it’s how emotional systems maintain stability. Remember: when one part of a system changes, other parts respond. If you try to exercise more or less, your workout clothes don’t react. With relationship patterns, you’re dealing with other people’s responses, as well as yours.

2. Limited practice opportunities. Creating a new pattern takes repetition, but most couples don’t want to argue ten times an hour, four times a week, to practice being less reactive. The level of practice that habit formation requires is hard to create for relationship work.

3. Variable intensity. Regular habit formation involves similar effort levels. Relationship events vary dramatically in intensity. For example, deciding where to eat out differs from deciding what groceries to buy because of money issues. Intensity depends on the type of relationship and the type of event. The overall level of stress in you and the system is also a factor.

Dr. Bowen observed that if your behavioural change represents true self-definition, this will get a reaction from the system. Any change representing substantial self-definition will trigger a system response. Even something like a new fitness routine can lead to reactions if it represents genuine self-definition in the relationship.

Why the timeline is extended: Your emotional reactions developed through years of repetition in stable relationship exchanges. Neural pathways and emotional reciprocal functioning have organized around existing patterns. When someone responds differently, all system levels—including neural firing patterns in you and others—require time to reorganise. The physiology needs time to adapt. Without regular practice opportunities, the process extends further. However, if you maintain your change, the system will adapt.

Defining self – creating a new habit

The habit research suggests three ideas for defining yourself more in our relationships:

First, automaticity develops through repetition in stable contexts. Brushing teeth becomes a habit through daily practice in the same bathroom. Managing reactivity becomes more automatic through a similar process. Repeated, intentional efforts in the actual interactions where the old pattern gets triggered. In what situations do you get more reactive? Can you find a more repeatable situation to focus on and learn to recognise that?

Second, self-chosen goals increase persistence and success. Singh and colleagues found that habits people selected for themselves strengthened faster than habits assigned by others. This is what defining oneself is about; it’s for you alone. What changes to you want to make because it’s important to you? The focus needs to come from your thinking about how you want to be in the relationship.

Third, emotionally neutral practice builds capacity. The research noted that morning routines and small preparatory habits eased the formation of more challenging behaviours. In relationship systems, comparable low-intensity practice helps build tolerance for the anxiety that accompanies change. Intentionally being a little reactive, especially when reactivity is lower, is important. It creates the neural circuits that notice reactivity and shift to being less reactive.

Preparatory work involves defining how you want to behave in situations. For example, parents can often have an over helpful focus on a child. Consciously thinking about situations where you can let go of this overfunctioning would be good preparatory work. Think of the situation and how you want to respond. Maybe you’ll say, “I’m sure you’ll figure it out,” or, “You got this”. Or maybe you need to remind yourself that they got this; let it go!

Think for a moment: What patterns show up regularly in your important relationships? Where might you practice a different response in less intense moments first, before attempting change in the most difficult interactions?

The differentiation process over time

Understanding a timeline for developing new automatic functioning can help maintain realistic expectations during the predictable challenges of systems oriented change.

The recognition phase: Change begins with observing the behaviour you want to change. Defining a specific pattern to observe marks the transition from general awareness to focused work. Getting good at noticing a pattern is the first step. When I began my work, I didn’t notice things until hours after the fact. That timeframe shortened. Eventually, I could recognize a pattern as it emerged and interrupt it.

This phase can bring increased anxiety. You might notice how automatically you accommodate your partner’s preferences while suppressing your own, for example. Thinking about changing this may create anxiety. Change often involves some discomfort, so don’t let that stop you.

Early repetition: According to Singh and colleagues, the largest gains in habit strength occur during the early repetition phase, yet this is also when the new behavior feels most effortful and inconsistent. In relationship systems, this happens when deliberately choosing different responses in triggering situations. Examples could be, pausing before reacting or staying present when the impulse is to distance.

These early attempts feel awkward and require conscious intention. The old pattern remains the brain’s default, so mistakes happen. You’ll miss opportunities. So having a replacement behaviour is useful. Being clear about how I wanted to act in a situation helped me. Telling my self, don’t do X, doesn’t tell me what TO DO. Planning to do Y instead of X gives the brain the direction it needs.

Emerging automaticity: This is when you notice the new pattern feels more spontaneous and requires less deliberate effort. The pause before reacting becomes more natural. Staying connected under tension feels less forced. When the tension is lower, this is more likely. In more intense situations, the old pattern can persist. That’s because you haven’t practiced at a higher intensity. Be patient.

Consolidation: With enough repetition, at some point new functioning feels more like an inherent part of how you operate. However, there is an important difference here from normal habit formation. Emotional reactivity varies with levels of stress, system stressors, relationship importance, and the importance of the situation. You will notice that it’s harder to sustain the new pattern when the emotional intensity is higher. You just need further practice.

How one does under pressure is an important measure of level of differentiation. A well-differentiated person can hold on to self even in very intense situations while staying connected. More intense situations are an opportunity to step up. However, I would NOT suggest creating a crisis to practice!

Remember that you are changing the system by changing how you respond to it. Dr. Bowen wrote about how the system can push to have you revert to your normal pattern. This can make sustaining change harder. But he observed that the system will adapt if the individual stays the course.

Making use of this research in your life

Start by picking one item you would like to change. Then just observe. How well can you recognize when the pattern happens? What is going on that gives rise to the pattern? Perhaps there is a feeling or some thinking that you can notice to alert you to the pattern. A medium level of intensity can be the easiest to notice. If it’s too subtle, you’ll miss it. If it’s too much, your automatic response will be too strong, and you won’t notice until after the fact. But that’s okay.

Your old reactions or anxiety aren’t going to go away completely. Progress can be measured by the increasing frequency of better functioning. Any amount of being less of what you don’t want and more of what you want is a win. Acknowledge that!

When professional support helps

Making these changes for more intense patterns can be hard. Working with a counsellor trained in Bowen family systems theory can provide a framework for this work. A counsellor can help you identify your patterns in key relationships. They will support you in defining areas for being less reactive and defining self more. Getting coached on the predictable ways that emotional systems resist change will help you persist. Finally, they can help you understand genuine progress.

The research on habit formation shows that meaningful change takes months. Having knowledgeable support during this process can make the difference between giving up and persisting.

A systems view of maturity and change

Neuroscience and Bowen Family Systems Theory agree: changing automatic behaviors takes time and repetition. It takes more than thinking to change a relationship pattern. You must practice new responses in the relationships where the problems exist. This process is slow—often slower than people expect. Understanding is important as it can support the conviction needed to persist. Differentiation requires conviction, action, and time.

While it’s hard work, I have found it to be worthwhile. As has my family!

Dave Galloway

I appreciate your interest in thinking systems.

You can reach me at dave.galloway@livingsytems.ca

For more on Bowen Family Systems Theory, go here.

Check out our podcast series on Spotify or YouTube.

Reference:

Singh, B., Murphy, A., Maher, C., & Smith, A.E. (2024). Time to Form a Habit: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Behaviour Habit Formation and Its Determinants. Healthcare, 12(2488). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232488