Chronic Anxiety: something for everyone.

Chronic anxiety is the outcome of the emotional programming that occurs for everyone, mostly from their family of origin. Learning how to be and what to pay attention to early in life programs our type and level of vigilance. Like a shadow, it’s always there. For example, there is a large body of research that supports the finding that early childhood adversity affects the programming of the stress response system. To put it another way, our family programmed our level of sensitivity into our physiology. And they taught us what to be sensitive to.

What’s in your programming?

Another aspect of programming results in learning how to feel, think, and act in relationships. We learn what achieves the highest level of comfort or the lowest level of discomfort. In addition, the more important the relationship is, and the more sensitive one is, the more this occurs. How to get attention and approval, how to stay out of trouble, and how to avoid punishment are examples of this vigilance. This occurs at a very young age and it “wires” the nervous system with habitual automatic ways of feeling, thinking, and acting. For example, at five, I remember feeling good because I “made” some older boys happy. I traded my smaller dimes for “bigger” nickels. Bigger is better, right?

The result was my orientation to “please others” and “make peace” became habitual and normal. As I got older, I started working on myself. I came to recognize a level of vigilance towards others that was oriented to “what does other want.” Thus, I had a chronic level of low-level anxiousness. I think of it as vigilance towards pleasing others. It felt normal.

Covid programming and chronic anxiety.

I believe we can see an example of this process with one’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. What we have learned, combined with our level of sensitivity, has created a level of anxious vigilance about Covid-19? For example, our default behaviours change: maintaining the right distance from others, automatically putting on a mask, paying more attention to how we are feeling for example. Your “family” including peers has taught you how to be with Covid-19 and in relationships regarding Covid-19. The anxiousness in one family member can and had infected the other family members. Entire family members behave according to the most vulnerable member (for good reason in my opinion). Overall, there is a range of responses based on the average level of anxiousness in the group.

Dr. Kerr writes about this (see reference) as learning “ranging from the seemingly osmotic absorption of parental anxieties to the incorporation of subjectively determined attitudes that create anxiety” (p.115). Children do their very best to adapt and cope with the environment that they are raised in. As an adult, these coping mechanisms, the emotional programming, may not be as adaptive. The result is that the constant vigilance of how to be in a relationship creates its own chronic anxiety.

Kerr also wrote: “So while moderately differentiated people can have a relationship in calm balance, their sensitivity to words and actions that appear to threaten that balance results, over time, in the relationship’s spawning an average level of chronic anxiety that is higher than that of a better differentiated relationship” (p. 76).

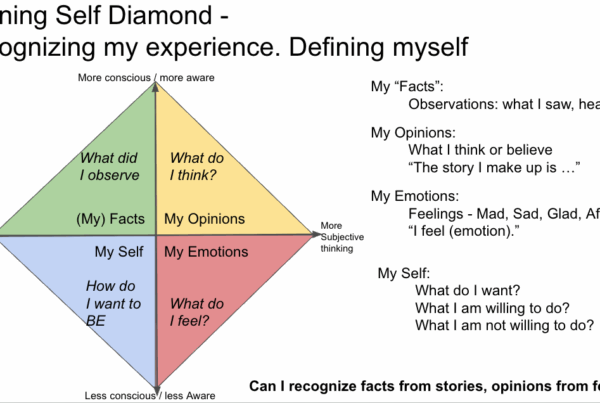

Defining Self to reduce chronic anxiety.

If not addressed, chronic anxiety can strain the relationship creating more tension. However, chronic anxiety originates from learned processes, which can be unlearned. Individuals are sensitive to the “state” of their relationships. This means we have a strong sense of knowing when there is a lack of agreement or approval, or some level of expectation or distress, especially in important relationships. It is our reactivity to the state of the relationship, because of our “learning”, level of vigilance, and level of resulting chronic anxiety, that is the challenge (p. 113).

Learning to change our response.

The chronic nature of chronic anxiety makes it more of a process about how one responds to imagined threats to the relationship. The eldest child may have learned to be over-responsible for others. They learned that adhering to rules, “being good”, not asking for much, and getting others to do the same was the way to get positive attention and approval. This turns into over-functioning in relationships. Importantly, the constant vigilance towards others puts a strain on any relationship. But if the eldest child can begin to focus on how they want to be and let their partner be responsible for themselves, they can unlearn the orientation and behaviour that leads to chronic anxiety.

Learning takes time and effort.

The processes involved with chronic anxiety are hard-wired habitual behaviours. And like other habitual behaviour changes, changing them takes time and effort. Significantly, the changes involve defining self, and this is the path to reducing chronic anxiety. Given the benefits of doing this makes me believe that the effort is worthwhile. What do you think?

Dave Galloway

dave.galloway@livingsystems.ca

The phrase “chronic anxiety” only occurs four times in Dr. Bowen’s book. Dr. Kerr has a chapter on chronic anxiety in his book Family Evaluation. His chapter 5 was the reference for this post. Find out more here.

Watch a video with Dr. Kerr on Chronic Anxiety here.