Vent Responsibly: Transforming Emotional Venting

When someone says “I need to vent,” what’s actually happening? This common phrase signals something deeper than a simple conversation. Let’s explore how one can transform venting into something productive. Please bear with me on this post, it’s longer than usual!

What’s Really Happening When We Vent?

Venting isn’t just complaining. It’s often part of a complex emotional process that serves several purposes.

Sometimes people vent without seeking solutions. They want to express negative emotions like frustration or disappointment. This might feel good momentarily, but it rarely resolves anything.

Venting frequently involves triangling by bringing a third person into an emotional situation. Instead of addressing issues directly with the source, we turn to someone else. Why do we do this?

The answer lies in how we manage discomfort, especially emotional discomfort. I use discomfort as a catchall for feelings like anxiety, frustration, tension, anger, exasperation, to name a few. It is a fact that expressing emotions to another person can provide temporary relief. Scientists call this social buffering. We share our distress to distribute the emotional burden. This is a key concept in Bowen Theory and how emotional systems work.

Have you noticed how much better you feel after telling someone about a problem? This relief happens even when nothing about the situation changes. So it has some benefits.

The Venting Intensity Engine

Emotional intensity drives the entire venting process. Two key factors determine this intensity:

The first is the level of physiological activation one experiences. This reflects the biochemical responses to whatever is bothering us. Stress hormones like cortisol surge through our systems, heightening our sense of urgency and vigilance towards threats. When strong enough, this physiological reaction of our emotional system punches into our awareness as feelings. In fact, Lisa Feldman Barrett would say that the brain chooses the feeling to go along with the physiological state the brain is sensing.

Emotional valence – positive or negative – influences our perceptions and subjective experiences. Negative emotions typically drive venting behaviours more strongly than positive ones. Together, these forces create a powerful influence that affects how subjective our thinking is.

Our perception of how situations impact us adds another dimension to this process. We develop a story (a narrative) about what events mean for us personally. Sometimes these stories are accurate. Often, they contain distortions shaped by our emotional state because that influences how we perceive things.

As intensity increases, our storytelling becomes more elaborate and subjective thinking becomes more pronounced. Our thinking can be more distorted. The facts of situations become less important than our interpretations and feelings about them. This cycle can amplify emotions rather than resolve them. The far end of the continuum of this is paranoid delusions.

Venting’s Usual Outcome

Without intentional intervention, venting follows a predictable pattern with limited benefits. One person expresses negative emotions to another, creating momentary relief. Yet, the underlying issues remain unaddressed. The original feelings are often there, but less intense.

Both parties can leave these exchanges feeling more validated in their original perspectives. Each believes they are “more right” than before the conversation began. Little genuine insight or personal growth emerges from these interactions. Being right and feeling better trumps reality.

The process frequently reinforces polarizing positions. Blame increases while personal responsibility decreases. We settle into predictable stories: “They’re wrong, I’m the victim, I’m helpless to change anything.” This pattern allows one to avoid the reality of the situation and what one might have to do to change it. It solves nothing and can add to an underlying frustration that can negatively affect other areas of one’s life.

Thus, with venting, the emotional energy dissipates temporarily, but without resolution, it eventually rebuilds. The cycle continues without producing meaningful change or growth. We feel better momentarily, falsely confident or self-righteous, but remain stuck in the same patterns.

Here’s an example that we can develop below. Chris is upset with Pat after having what Chris calls an argument. Chris calls you and starts by saying, “You won’t believe what just happened. Pat can be such a jerk!” You want to support Chris, so you reply, “Wow, tell me more.” A ten-minute venting of how bad Pat is and how much Chris is a victim ensues. You notice that you have started to think Pat was all wrong.

A Better Approach to Vent Responsibly: The Differentiation Diamond

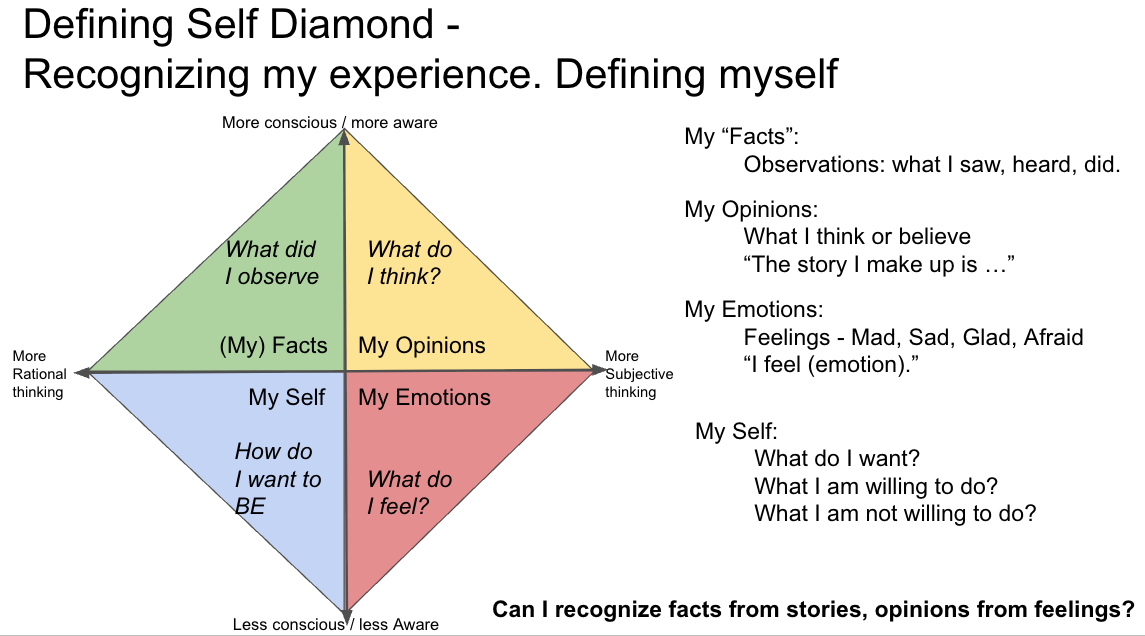

There’s a more functional way to handle emotional discomfort. A more objective approach can help clarify the situation. One method is to use the Differentiation Diamond. This framework provides structure to our emotional expressions while maintaining personal responsibility. The process has four parts, each to help us be more factually and emotionally objective. The focus is on self and being more objective. It asks an individual to think about “What can I do instead of venting?”

I Can Share My Understanding of Facts – Objective Reality

This starts with what is objective and factual about the situation. The goal is to ground your conversation in observable facts that anyone could witness if they went through your experience. Factually, what happened, not your interpretation of it. Consider the measurable impact these events had on you. Ask yourself: “What happened to me that anyone else would also have witnessed?” This question helps you separate objective events from your (mental) interpretations.

Here’s an example. Chris and Pat are partners. Pat had spent money that wasn’t within their budget. Because of the desire to buy a house, Chris has serious money concerns. They exchanged words (aka an argument) about this. Chris could objectively say the following. “Pat’s voice got louder. Pat said, ‘Stop nagging me’. The look on Pat’s face changed. Pat moved out of the room”. These are observable facts of functioning that anyone else could have observed. The subjective version of this might be this: “Pat was angry and shouted at me and then stomped out of the room, acting like a baby.”

I Can Share What I Think – My Opinions

Your thoughts and opinions matter, but recognizing them as only your subjective thinking is crucial. Using I, express what you don’t like about the situation, what expectations you held, and what beliefs inform your perspective. Remember that you actively choose which opinions and judgments to hold on to. You have the power to revise or discard thoughts that don’t serve you well. Your thoughts aren’t immutable truths, but perspectives you can refine. Judgements are opinions, not truths. (They might be your truth, but not the TRUTH).

Continuing our example, Chris might say, “I thought Pat was shouting and was angry. I could tell by the look on his face and what he said. I don’t believe adults stomp away like children.”

These are opinions, judgments, and interpretations. Some of it might be accurate. The brain will react accordingly by holding on to these ideas (beliefs). In this case, it will create the physiology for responding to an angry, shouting person stomping away from you.

A more neutral way of describing the situation could be: “I assumed Pat was angry by the look on his face, his words and tone of voice. Pat appeared to be upset when leaving the room. I know that’s my story. Something else might be going on.”

I Can Share What I FEEL

Feelings and the emotions that foster feelings add depth to our experiences, but differ from thoughts. True feelings centre on basic emotional states that we name as: mad, sad, glad, angry, frustrated. Many people struggle to differentiate thoughts from feelings. When you say, “I think that’s wrong,” you’re expressing an opinion. When you say, “That makes me angry,” you’re describing a feeling that is a label for an emotional state. (A better statement would be I feel angry in situations like this. Dr. Bowen distinguishes between emotions and feelings.

Feelings arise automatically. I don’t believe we can stop this. However, one can decide how to respond to situations instead of being reactive. This doesn’t diminish the validity of feelings, but emphasizes your agency in our responses. The same event can trigger different feelings based on how one frames it and chooses to respond. The main point is to recognize and separate feelings from interpretations and judgments. This helps one be more thoughtful and response-able.

Continuing the example, Chris might say: “When I heard about how much Pat spent, I felt frustrated, and then I felt angry. I now think I interpreted what was happening as a threat, like we’ll never get a house. I also was feeling rejected. Being alone creates anxiety in me. I guess I felt threatened, so I got angry.”

I Can Share What I Would Like

Expressing desires and wants form another critical aspect of communication. Express what you would like to happen while recognizing these preferences as opinions rather than universal truths. For example, I believe I can want anything, but nobody owes it to me. This mindset allows one to state preferences without making demands, opening a space for discussion rather than confrontation. It recognizes responsibility for self over expectations towards others.

Chris might then say, “I want to talk to Pat about what happened. I could have handled this better.”

I Can Share How I Want to BE

Perhaps most importantly, define your values and convictions in relation to the situation. Consider what principles matter most to you and what actions align with your authentic self. Given the circumstances, clarify boundaries around what you’re willing to do or not do. This component connects your response to your deeper sense of identity and purpose rather than merely reacting to external events.

Again, Pat could respond, “I want to be a person who can have thoughtful discussions about differences. I don’t think partners have to agree on everything. I want to be a partner who can be for self without being selfish and be for others without being selfless.” (Dr. Kerr’s phrase)

Defining Self to Vent Responsibly Using the Diamond

One can work at a deeper level with the Differentiation Diamond. The above was working more at a cognitively conscious level. The following works to understand the underlying emotional process. This is often non-conscious until one intentionally reflects on it. Use it to examine your own role in a situation. Again, the focus is on self and defining self.

How Did I Participate?

* What observable behaviours did I contribute?

* What actions have I taken to prevent or resolve the issue?

* Focus on functional facts: observable actions and behaviours, not intentions or thoughts.

How Did I Think? What Stories Do I Have?

* What judgments do I hold about this situation?

* What interpretations and stories did I make up?

* What could I do differently about my judgments and stories?

How Did I Manage My Feelings?

* How reactive am I being?

* How did my reactivity contribute to the situation?

* How are my feelings influencing my thinking?

* What am I really worried about or afraid of?

* Am I blaming others or myself to avoid something?

How Can I Define Myself in This Situation?

* How do I want to BE given these circumstances?

* What principles or values matter most here for me?

* What am I willing or unwilling to do given the situation?

* What did I have to work on so I don’t get this reactive?

In our example, Chris might realize they were being critical of Pat because of their anxiety about money. Past struggles with money in Chris’s family have created a strong desire for financial security. Chris finds Pat’s unplanned spending threatening and frustrating. Chris now understands that this underlying emotional process is for Chris to manage. One way to manage this is to have an open conversation (good emotional contact) with Pat about Chris’s past and how it affects the present. Chris also recognizes that fear of conflict over money, and not wanting to break up the relationship because of money, has kept Chris from talking about it. Chris now understands that the argument wasn’t about Pat’s purchase, but more about Chris’s underlying emotional process about money and conflict. This isn’t just about Chris; Pat plays an equal part in this dynamic!

Moving From Immature to Mature Expression – Venting Responsibly

When we don’t like something – for example, the effort required, the hassle involved, or unmet expectations – there’s usually some underlying threat. Ask yourself, “What is it?”

Immature venting shows up as blaming, helplessness, victimhood, less self-responsibility, and low tolerance for discomfort. Or when minor inconveniences (“my coffee was too cold”) trigger disproportionate responses.

Mature venting would include the following. I can express my displeasure with less negativity. I manage my reactions so that my emotions do not infect others. Personal impact, rather than external blame, is my focus. Finally, one could share their thinking about what they plan to do. Getting another person’s opinion regarding one’s reactivity and action plan might be helpful.

The next time you feel the urge to vent, try the Differentiation Diamond approach. You might discover that understanding your role in the situation leads to growth rather than temporary relief.

This approach could lead to very different discussions with your friends.

Dave Galloway

I appreciate your interest in thinking systems.

You can reach me at dave.galloway@livingsytems.ca

For more on Bowen Family Systems Theory, go here.

Check out our podcast series on Spotify or YouTube.