A Self-Reflection Guide Based on Bowen Family Systems Theory

A familiar scene

A husband comes home after a hard day. His wife asks how he’s doing. He says “fine” in a tone that says otherwise. She presses. He snaps. She withdraws. He feels guilty and pursues. She’s now irritated. Within minutes, they’re in a familiar dance neither of them chose.

What happened? The two nervous systems activated each other. Two people, each reacting to the other’s reaction, with very little thinking involved. In Bowen theory, we’d call this emotional process. It’s when your reactions are driven more by the emotional field around you than by your own thinking.

I see versions of this pattern constantly. In families I have worked with, and if I’m honest, in my own relationships when stress is high and I’m not paying attention.

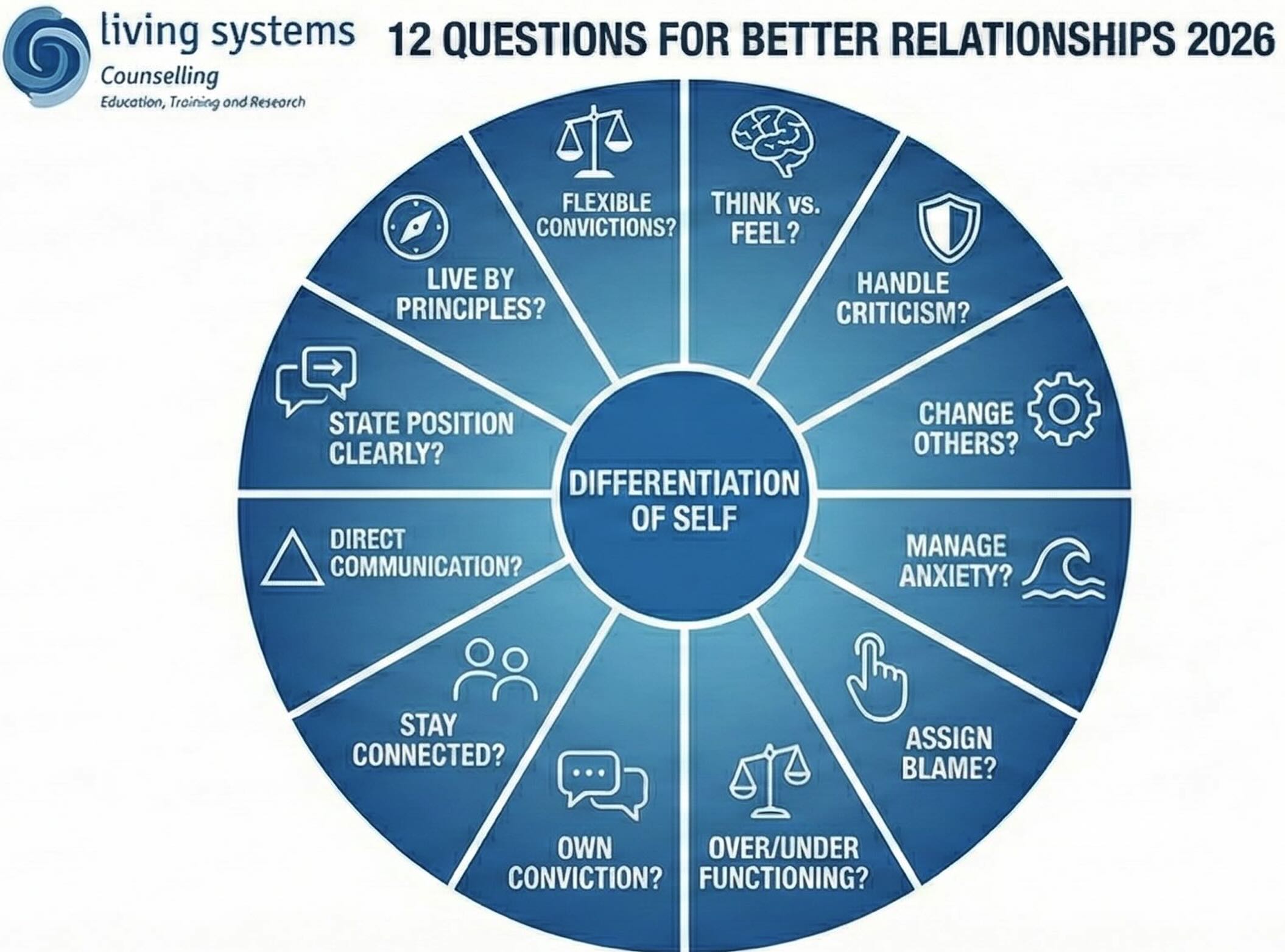

Differentiation of self framework

The psychiatrist Murray Bowen spent decades observing families and developed a way of thinking about these automatic patterns. One of his central ideas is differentiation of self. This is the degree to which a person can maintain their own thinking, beliefs, and direction while remaining close to the important people in their lives.

Bowen observed that people differ in this capacity. Some make major life decisions based primarily on what feels right in the moment or on gaining approval from others. Others can hold on to their convictions even when facing pressure to conform, while staying engaged with family or others. These patterns often trace back to our families of origin and the relationship systems where we first learned how to manage closeness and distance.

I find the family systems framework useful because it gives me something concrete to observe in myself. This post is written for anyone interested in doing the work of noticing their own patterns in relationships and considering what different functioning might look like. You don’t need a clinical background. You just need curiosity about yourself.

An important note: These questions point toward aspirational functioning. No one operates at the highest level all the time. I certainly don’t. We all move up and down depending on stressors and fatigue. The goal isn’t perfection; it’s increasing awareness of these patterns so we can work on them.

You could work through these, one per month in 2026. Or do one per week and then take a week off. Repeat for the next three quarters. It’s not a race, or a contest. We all do the best we can.

This is lifelong work.

Working through these questions

I’ve arranged these twelve questions in a sequence that builds on itself. The first phase focuses on getting clear about your own thinking. What you actually believe, independent of emotional pressure and outside authority. The second phase involves observing the part you play in your relationship patterns. Only after developing some clarity and self-observation does it make sense to focus on the third phase: working on actual change.

Trying to change behavior before understanding your own thinking and seeing your patterns clearly produces temporary shifts that don’t hold.

The sequence matters.

Phase one: Getting clear on your own thinking

Before you can work on relationships, you need some clarity about what’s happening inside your own head. These first four questions address that foundation.

1. Do I know the difference between what I feel and what I think?

Many people use “I feel that…” when they mean “I believe that…” and treat the two as interchangeable. But feelings and intellectual assessments are different systems—they appear to operate through different processes in the brain. A person working toward greater differentiation develops the capacity to recognize when they’re having an emotional response versus when they’ve arrived at a reasoned position.

Both matter. Confusing them leads to trouble.

I notice this in myself when I’m convinced I’ve thought something through, only to realize later that I’d arrived at my “conclusion” within seconds—far too fast for actual thinking. That’s usually feeling dressed up as thought.

Reflection: Think of a recent decision or opinion you hold strongly. How quickly did you arrive at it? Was there time for actual thinking, or did the conclusion come first?

2. Do I take positions based on my thinking, or do I rely on outside authorities to justify my choices?

Less differentiated people tend to invoke external authorities such as cultural values, experts, rules, science taken out of context, to support positions they hold for emotional reasons. More differentiated functioning involves being able to say, “I believe this because…” and own the reasoning, rather than hiding behind “Science says…” or “Everyone knows…”

This doesn’t mean ignoring expertise. It means knowing the difference between “I’ve considered this and here’s what I think” and “I’m borrowing someone else’s authority because I haven’t done my own thinking.”

Reflection: Pick a position you hold on a contested topic. Can you articulate why you believe it in your own words, based on your own reasoning, without citing an authority?

3. Can I hold on to my convictions without becoming dogmatic or rigid?

Bowen described more differentiated people as “always sure of their beliefs and convictions but never dogmatic or fixed in thinking.” They can hear and evaluate other viewpoints and revise their positions based on new information.

The key distinction is between having a solid sense of self and having a rigid, defensive posture that can’t tolerate challenge.

I think of it this way: certainty that can’t be questioned isn’t strength. It’s brittleness.

Reflection: When was the last time you genuinely changed your mind about something based on new information or another person’s perspective? What made that possible?

4. When someone criticizes or praises me, how much does it affect my functioning?

Bowen described more differentiated people as “sufficiently secure within themselves that functioning is not affected by either praise or criticism from others.” This doesn’t mean becoming indifferent or cold. It means having enough internal stability that external feedback, positive or negative, doesn’t send you into a tailspin or inflate you beyond reason.

How solid is your internal ground?

I notice my ground gets shakier when I’m tired or stressed. Criticism lands harder. Praise feels more necessary. That’s useful information about my current state.

Reflection: Recall a recent instance when someone’s opinion of you, positive or negative, affected how you felt about yourself. How long did the effect last? What does that tell you?

Phase two: Observing the part you play

Once you have some clarity about your own thinking, the next step is an honest observation of your patterns in relationships. This isn’t about self-blame; it’s about seeing how you function in the systems you’re part of.

5. How much of my mental energy goes toward trying to change other people?

Less differentiated functioning involves a significant investment of “psychic energy” in directing the life of another person. This can show up as trying to fix them, improve them, or get them to see things “correctly”.

Where does your mental energy actually go during the day? How much time do you spend thinking about what someone else should do differently?

When I catch myself composing mental arguments for why someone else is wrong, I try to notice it. That’s energy I could put elsewhere. The pattern is worth seeing before trying to change it.

Reflection: Over the next few days, notice when your thoughts turn to what someone else should do, think, or understand. How much of your mental space does this occupy?

6. When my family or social group is anxious, do I absorb that anxiety or can I remain relatively calm?

Emotional process moves through relationship systems. When one person is anxious, others often become anxious in response. This is emotional reactivity, and it isn’t just psychological. Anxiety is contagious at a physiological level. Our nervous systems are wired to pick up threat signals from others.

A person with more differentiation has a greater capacity to be present with anxious others without “catching” the anxiety. They can stay thoughtful when others are reactive.

Reflection: When someone around you gets upset, what happens in your own body? Does your heart rate increase? Does your breathing change? Do you automatically match their emotional state?

7. When things go wrong in my relationships, how quickly do I assign blame?

Less differentiated functioning involves holding others responsible for one’s own happiness and wellbeing. When something doesn’t work, the reflex is to identify what the other person did wrong. This kind of emotional reactivity—the automatic move to blame—is worth noticing.

Notice your first response when conflict arises. Is it to look outward or to consider your own contribution?

Observation comes before change.

Reflection: Think of a recent conflict or disappointment in a relationship. What was your first internal response? How long did it take, if at all, before you considered your own part in it?

8. In my closest relationships, is there flexibility in who does more and who does less, or have we become locked into fixed patterns?

There’s a reciprocal pattern Bowen called overfunctioning and underfunctioning. In many relationships, one person compensates for perceived deficits in the other, which then reinforces those deficits. The overfunctioner takes on more responsibility; the underfunctioner takes on less.

Both positions represent a lower level of emotional functioning. The overfunctioner loses self by defining their worth through managing others. The underfunctioner loses self by letting others define their capabilities.

Can you see where you land in this pattern? I know my tendency is toward overfunctioning. I can take on responsibility that isn’t mine. Seeing the pattern doesn’t make it disappear, but it gives me something to work on.

Reflection: In your closest relationship, who takes on more responsibility? Has this shifted over time, or has it become fixed? What’s your part in maintaining the pattern?

9. In my family, do problems get addressed between the people directly involved, or do they get routed through third parties?

Bowen identified the triangle as the basic building block of emotional systems. When tension rises between two people, there’s a pull to involve a third. This can be with a child, another family member, or a friend.

Observe how issues move through your family system. When you’re upset with someone, do you talk to them directly, or do you talk to someone else about them?

Most of us do both, depending on the situation. The question is whether you can see the pattern.

Reflection: Think of a current tension in an important relationship. Have you talked to the person directly about it? Have you talked to others about it? What would it take to address it directly?

Phase three: Working on change

With clarity about your own thinking and honest observation of your patterns, you’re in a position to work on actual change. These final questions point toward different functioning.

10. When I disagree with someone important to me, can I state my position clearly without attacking theirs?

A more differentiated person can articulate what they believe with no need to criticize or undermine what the other person believes. They can say “I think…” or “I’ve decided…” without adding “…and you’re wrong.”

This isn’t about avoiding conflict. It’s about being able to hold a position that belongs to you, stated on its own merits. Without imposing it on the other person.

This is a learnable skill. It requires the groundwork of the earlier questions.

Reflection: Think of a disagreement you’re currently navigating. Can you state your position in two or three sentences without referencing what’s wrong with the other person’s view? (Or referring to others to “prove” you are right!)

11. Can I stay connected to family members I disagree with, or do I need distance to manage the relationship?

One pattern Bowen identified was using physical or emotional distance to manage intensity in relationships. Some people cut off from family members rather than working out a way to remain in contact while holding different positions.

More differentiated functioning involves the capacity to stay in relationship with people whose views or choices differ from yours, without either merging with their position or needing to exit entirely. Merging means abandoning your own views to keep the peace. Exiting means you can only hold your position by leaving.

This is advanced work. I don’t think anyone does it perfectly.

Reflection: Is there a family member you’ve distanced yourself from? What would it look like to remain connected while still holding your own position? What makes that difficult?

12. Am I living according to principles I’ve thought through, or am I primarily reacting to circumstances?

Bowen described more differentiated people as “principle-oriented, goal-directed.” They’ve thought through what matters to them and make decisions accordingly. Less differentiated functioning is more reactive. It is responding to whatever pressure is most immediate, trying to keep others happy, or doing what feels comfortable in the moment.

This last question is the broadest: Are you steering your life or being steered?

Reflection: What are three principles that guide how you want to live? When did you last make a decision based on those principles rather than on comfort, approval, or pressure?

Differentiation of self as ongoing work

Bowen placed human functioning on a continuum. He never saw anyone at the theoretical top quarter of his scale, and he was clear that movement toward greater differentiation of self is slow, hard work that takes years. The patterns we developed in our families of origin run deep. They’re wired into our nervous systems.

The value of these questions isn’t in producing a score or a self-diagnosis. It’s to increase awareness of the automatic patterns that operate in all of us. When you can observe your own functioning more clearly, you have more choice about how to respond.

Bowen theory also emphasizes that you can only work on your own differentiation. The work is always on self, not on getting others to change. Paradoxically, when one person in a family system functions at a higher level, the entire system often shifts in response.

These are questions worth returning to periodically. Your answers will likely change depending on what’s happening in your life and relationships. The goal isn’t to arrive at a final destination but to keep working at the task of becoming a more defined, more responsible, more thoughtful person, while staying connected to the people who matter to you.

If you’d like to explore these patterns with support, counselling can provide a space to work on differentiation in the context of your own family and relationships.

I believe that a world of people working to be more differentiated would be a good think.

Every effort to function better is a step in the right direction. I wish you luck in your efforts in 2026!

Thank you for your interest in family systems.

Comments are welcome: dave.galloway@livingsystems.ca

Learn more about Bowen Theory here.

Living Systems is a registered charity, and we provide counselling services to low-income individuals and families. You can support our work in several ways: